In a world where the pursuit of knowledge is more vibrant than ever, EduMple stands out as a beacon of clarity and simplicity in the complex landscape of educational resources. As learners of all ages navigate the choppy waters of information overload and rapidly evolving technology, EduMple has emerged as a revolutionary platform with a mission to demystify learning by breaking down complex concepts into easily digestible pieces. EduMple is built on the foundation that education should be accessible, straightforward, and enjoyable for everyone. It focuses on delivering high-quality educational content that is curated and designed by vetted experts to …

What the New Era of Education Looks Like, Thanks to COVID-19

As the COVID-19 pandemic rages on, parents and students are coming to the realization that traditional, classroom-style education is not necessary. In fact, some may take that a step further and say that the traditional classroom is more of a hindrance than a help when it comes to learning. Picture the typical schoolroom setting. One teacher presides over 30 or more students. Is this order or chaos? Most teachers will attest to the fact that a considerable amount of time is taken up each day trying to gain control of the classroom and then racing through the day’s lecture, trying …

Continue reading “What the New Era of Education Looks Like, Thanks to COVID-19”

The Edvocate Podcast, Episode 6: 8 Ways That Digital Age Teachers Avoid Burning Out

Being a teacher is a tough job. So much so, many new teachers end up leaving the field within their first three years. To ensure that the next generation of students have qualified teachers, we must nip this phenomenon in the bud. In this episode, we will discuss 8 ways that digital age teachers avoid burning out.

The Edvocate Podcast, Episode 5: The Archetype of a Great Teacher

One of the questions that I am frequently asked is, what does a good teacher look like? I respond by mentioning my 10th-grade Biology teacher, Mrs. Minor, and listing the attributes that made her the archetype of a great teacher.

The Edvocate Podcast, Episode 3: Why Teacher Shortages Occur

It seems that every year around this time, school districts around the country report not being able to fill all of their open teacher vacancies. Why do these cyclical teacher shortages occur? In this episode of the podcast, we will explore this topic in-depth.

Intelligence in America: Time to Test Something New

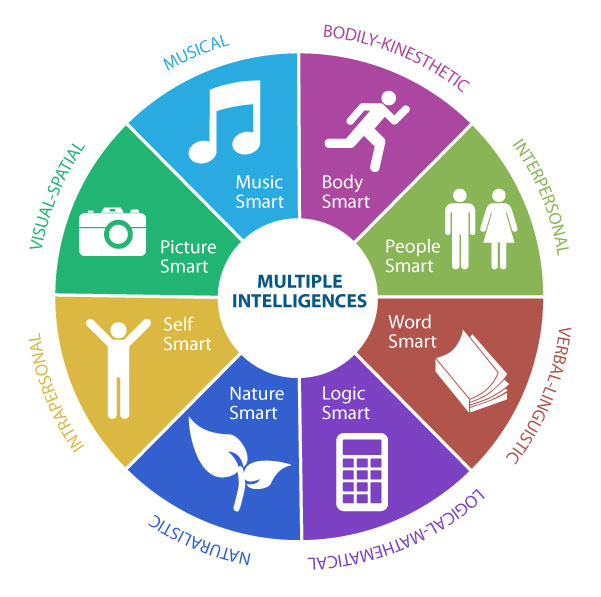

Measuring the progress of any endeavor requires a definition of success. Education, by its very nature, is difficult to ascribe a single definition of success; “making people smarter” is far too broad and subjective, while “increasing the IQs of students” is perhaps too esoteric and subject to debate over the role of genetics and other uncontrollable factors. Measuring progress is similarly fraught in the academic sector. Grades have been a target of considerable suspicion for some time now, and rightly so: everything from grade inflation to instructor subjectivity makes grades an altogether blunt and misleading metric. There again, what do …

Continue reading “Intelligence in America: Time to Test Something New”

What Preschool Can Teach Us About Choice and Opportunity

There is a pantheon of sitcom cliches that, no matter how many times they’ve been done before, always turn up in new ones. Among the repeat offenders: outrageously stressful wedding planning, pregnancy and baby delivery hi-jinks, new parents shopping for the “perfect” preschool, arguments over dolls vs footballs, and how these early childhood influences will determine the baby’s entire future from school choice to occupation and social status. The sad reality is that the last two of these absurd situations have a kernel of truth. Does getting into the right preschool really determine whether a given child will go to …

Continue reading “What Preschool Can Teach Us About Choice and Opportunity”

Disengaged Students, Part 20: Too Many Standards, Too Little Learning

In this 20-part series, I explore the root causes and effects of academic disengagement in K-12 learners and explore the factors driving American society ever closer to being a nation that lacks intellectualism, or the pursuit of knowledge for knowledge’s sake. Imagine a construction worker who arrives at work to find that his job is now subject to a new set of federal regulations in addition to the rules he has always followed. A few months later he is handed a stricter set of rules from the state. It does not contradict the federal regulations, but it places even higher …

Continue reading “Disengaged Students, Part 20: Too Many Standards, Too Little Learning”

Disengaged Students, Part 16: Too Much Parental Concern, But Not About Education

In this 20-part series, I explore the root causes and effects of academic disengagement in K-12 learners and explore the factors driving American society ever closer to being a nation that lacks intellectualism, or the pursuit of knowledge for knowledge’s sake.. Today’s parents are hyper-aware that parental actions in the formative years can lead to problems in later life, and the widespread disagreement about which actions are harmful leads to great stress and confusion . Raising children safely to adulthood is no longer sufficient to earn the label of a “good” parent. A glance at any handful of parenting blogs …

Continue reading “Disengaged Students, Part 16: Too Much Parental Concern, But Not About Education”

Disengaged Students, Part 15: Careerism vs. Intellectualism in K-12 Education

In this 20-part series, I explore the root causes and effects of academic disengagement in K-12 learners and explore the factors driving American society ever closer to being a nation that lacks intellectualism, or the pursuit of knowledge for knowledge’s sake. Parents want what is best for their kids and most will say that they just want them to be “happy.” Children’s education is important to parents, but so is the promise that they will get a job someday. Well-rounded approaches to education are not favored as strongly as focused learning programs that emphasize job skills and applications. Academic engagement, …

Continue reading “Disengaged Students, Part 15: Careerism vs. Intellectualism in K-12 Education”