In schools, common planning time refers to any period scheduled during the school day for several educators, or teams of educators, to work on grading and lesson planning. In most cases, common planning time is considered a form of professional development. Its primary purpose is to bring educators together to learn from one another and collaborate on projects to improve lesson quality and teaching effectiveness and learner achievement.

These improvements result from (1) the improved communication that occurs among educators who meet and talk regularly, (2) the insights and constructive feedback that happen during professional discussions among educators, and (3) the curriculum and resources that are created or improved when educators work on them collaboratively.

While the term suggests that the main activity of common planning time is “planning,” the time may be devoted to a broad variety of activities.

The following are a few examples of what generally takes place during common planning time:

Examining educator work: Teachers may collaboratively review lesson plans or assessments before being used in class and then offer feedback and recommendations for improvement.

Examining learner work: Teachers may look at examples of learner work turned in for a class and then offered recommendations on how lessons may be modified to improve learning and learner work quality.

Examining learner data: Teachers may analyze learner-performance data from a class to find trends—such as which learners are consistently failing or underperforming—and collaboratively develop proactive teaching and support strategies to help learners struggling academically. By discussing the learners they have in common, educators can develop a stronger understanding of certain learners’ specific learning needs and capabilities, helping them coordinate and improve how they are taught.

Examining Education Research: Teachers may select a text to read, such as a research study or an article about a specialized teaching strategy, and then engage in a conversation about the text and how it can help inform their teaching strategies or practices.

Developing curriculum: Teachers may collaboratively work on lesson plans, assignments, projects, and new classes, such as an interdisciplinary class taught by two educators from distinct subject areas (for example, an art-history class taught by an art educator and a history educator). Teachers may also plan or develop other learning experiences, such as capstone projects, demonstrations of learning, learning pathways, personal learning plans, or portfolios, for example.

Benefits and Challenges of Common Planning Time

The common planning time concept is not usually an object of debate. Still, skeptics may question whether the time will positively impact learner learning, whether educators will utilize the time purposefully and productively, or whether learners would be better served if they spent more time teaching.

Since it’s often extremely challenging, from a research perspective, to attribute gains in learner performance to anyone’s influence in a school, the benefits of common planning time may be challenging to measure objectively and reliably.

However, common planning time will be debated when the time is poorly used, when meetings become disorganized and unfocused, when educators have negative experiences during meetings, and when the practice is perceived as a burdensome requirement.

Like any school-improvement strategy or program, the design and execution quality will usually decide the results achieved. If meetings are poorly organized and operated, and conversations lapse into complaints about policies, or if educators fail to turn group learning into changes in teaching strategies, common planning time is less likely to be successful.

Benefits

Advocates of common planning time believe that it can foster and promote a broad variety of professional interactions and practices among educators in a school. For instance:

- Teachers may volunteer for leadership responsibility or feel a more profound investment in a school-improvement initiative.

- Teachers may feel more confident and better equipped to address their learners’ learning needs, and they may become more willing to participate in the type of self-reflection that leads to professional growth.

- The school culture may improve, and collegial relationships can become better and more trusting if the faculty interacts and communicates more productively.

- Teachers may participate in professional collaborations more often, such as co-creating and co-teaching interdisciplinary classes.

- More teaching innovation may take hold in classes and educational programs, and educators may begin incorporating efficient teaching strategies that are being used by colleagues.

- Teachers may begin utilizing more evidence-based approaches to constructing lessons and delivering instruction.

Challenges

When implementing common planning time, administrators and educators may encounter several challenges that could give rise to criticism or debate. For instance:

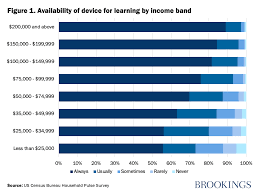

- Competing duties and logistical challenges can make the scheduling of regular common planning time challenging. Insufficient meeting time or randomly scheduled time may then undermine the strategy and its potential benefits.

- A scarcity of school leaders’ support could lead to an inadequate investment of time, resources, and attention.

- Poor training for group facilitators could produce ineffective facilitation, disorganized meetings, and an erosion of confidence in the strategy.

- A scarcity of clear goals for common planning time can lead to unfocused conversations, misspent time, and general confusion about the meeting’s purpose.

- A negative school or faculty culture can lead to tensions, conflicts, factions, and other issues that undermine the common planning time’s potential benefits.

- A lack of observable, measurable progress, or learner-achievement gains can erode support, motivation, and enthusiasm for the strategy.

- Divergent educational philosophies or learning styles can create disagreements that threaten the collegiality and idea of shared purpose usually required to make common planning time successful.