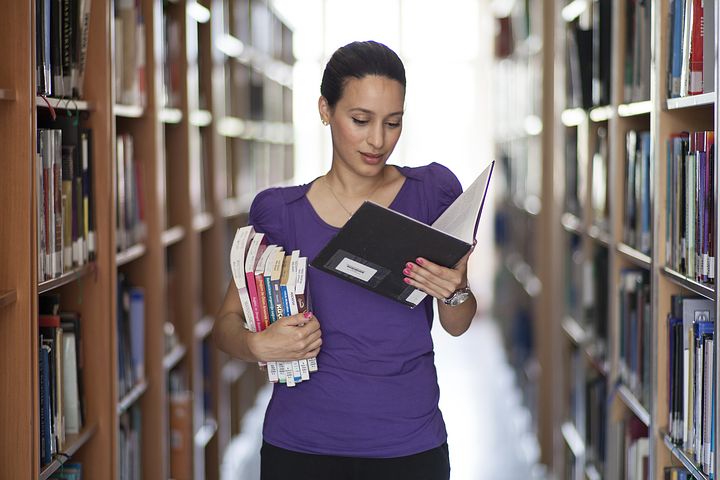

By Ruth Schoenbach and Cynthia Greenleaf Every day, middle and high school teachers ask their students to read and understand complex texts in disciplines such as history, literature, biology, or economics. Such reading is foundational to student success in school, the workplace, and in civic life. Yet, national tests results and our own eyes tell us that the majority of high school students aren’t getting it. How can teachers and administrators create classrooms where students routinely engage with challenging material, think critically about texts, synthesize information from multiple sources, and effectively communicate what they have learned? And how can we …

Disengaged Students, Part 3: The Role of Nationalism

In this 20-part series, I explore the root causes and effects of academic disengagement in K-12 learners and explore the factors driving American society ever closer to being a nation that lacks intellectualism, or the pursuit of knowledge for knowledge’s sake. The 20th century saw the rise of a new sort of anti-intellectualism in America, one stemming from a nationalist perspective. The idea that love of country trumped all other ideas and ideals was popularized during both World Wars, and exacerbated by the Communist paranoia and McCarthyism in the decades that followed. Speaking out against war or showing sympathy with …

Continue reading “Disengaged Students, Part 3: The Role of Nationalism”

How companies learn what children secretly want

Faith Boninger, University of Colorado and Alex Molnar, University of Colorado If you have children, you are likely to worry about their safety – you show them safe places in your neighborhood and you teach them to watch out for lurking dangers. But you may not be aware of some online dangers to which they are exposed through their schools. There is a good chance that people and organizations you don’t know are collecting information about them while they are doing their schoolwork. And they may be using this information for purposes that you know nothing about. In the U.S. …

Continue reading “How companies learn what children secretly want”

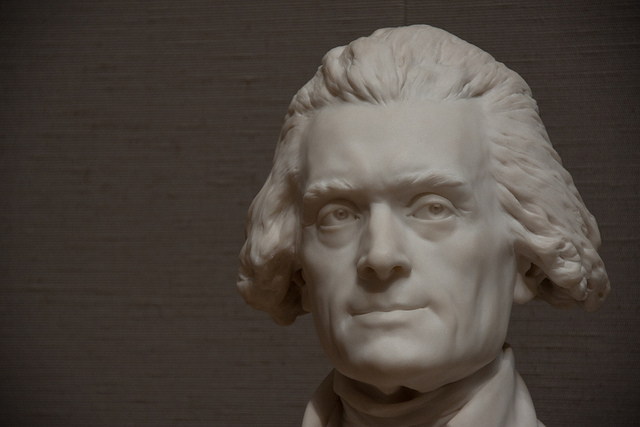

Disengaged Students, Part 2: The Anti-Intellectualism of Thomas Jefferson

In this 20-part series, I explore the root causes and effects of academic disengagement in K-12 learners and explore the factors driving American society ever closer to being a nation that lacks intellectualism, or the pursuit of knowledge for knowledge’s sake. It is easy to blame the rise of anti-intellectualism on the vagaries of the digital age, but in fact anti-intellectualism has been present in America from the beginning of our national history, and its roots lie in other civilizations. The Roman Republic had anti-intellectual overtones, particularly when it came to assimilation of new cultures. Roman culture was seen as …

Continue reading “Disengaged Students, Part 2: The Anti-Intellectualism of Thomas Jefferson”

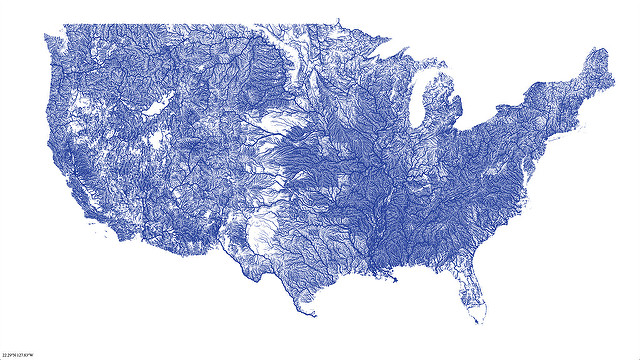

Disengaged Students, Part 1: How did American Anti-Intellectualism Begin?

In this 20-part series, I explore the root causes and effects of academic disengagement in K-12 learners and explore the factors driving American society ever closer to being a nation that lacks intellectualism, or the pursuit of knowledge for knowledge’s sake. Americans pride themselves on their high ideals. On national holidays Americans delight in quoting phrases like “all men are created equal” and “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” The ideologies of freedom of religion, democratic government, and socio-economic mobility are ingrained in American children beginning in pre-K educational settings. While these ideologies are admired from a distance, real …

Continue reading “Disengaged Students, Part 1: How did American Anti-Intellectualism Begin?”

Important Ways Assessment in the Classroom Impacts Testing and Curriculum

Assessment has become a central part of education. While lifelong learning should always be the main focus of a classroom, the pervasive knowledge that at some point, there will be testing, from the local scale to the national, has also become a backdrop in curriculum development. Standardized testing has long been part of the K–12 scene, but since the enactment of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) in 2001, student results have been used by the federal and state governments to determine the level of funding schools receive. The salaries and job security of teachers and administrators are also determined, at …

Continue reading “Important Ways Assessment in the Classroom Impacts Testing and Curriculum”

Another Failed Charter: Do These Schools have a Future?

In February of 2013, the Einstein Montessori School in Orlando became a casualty of the charter school experiment. State officials closed the school that had 40 students ranging from third through eighth grade. The school promoted itself as a specialty institution for dyslexic students but teachers told media outlets that there was no curriculum in place, no computers and no school library. Despite these and other red flags the school remained in operation longer than it should have because Florida law currently only allows for immediate school closures for safety, welfare and health issues. Of course parents of the students …

Continue reading “Another Failed Charter: Do These Schools have a Future?”