In this series, appropriately titled “Black Boys in Crisis,” I highlight the problems facing black boys in education today, as well as provide clear steps that will lead us out of the crisis.

There are plenty of black men who positively impact the young men coming up in their communities. Some are high-profile while others are local businessmen, or even teachers. As a general statement, however, black boys have less people to look up to and hold accountable than their white, and even other minority, peers.

Consider these statistics: Less than half of black males’ graduate high school on time. In 2008, only 11 percent of black males in America had completed a bachelor’s degree – and only half of the 4.6 million who had attended college had made it to graduation. Seventy-two percent of black children are raised in single-parent households and the national average is only 25 percent. Those single parents are more likely to be employed than the national average, but also more likely to live in poverty. Here’s a humbling stat on incarceration: 61 percent of the U.S. prison population is black or Latino.

School is a second home to K-12 students and black boys don’t have many role models who look the way that they do. Black males make up just 2 percent of the K-12 school teacher population. Less than 20 percent of U.S. teachers are not white even though minority students combined make up a majority of K-12 students. It’s not that educators who are female and white can’t have a positive impact on the lives of their students – they certainly can and do. There’s a difference between a teacher who has a different life viewpoint than you and a true role model. Black boys need to see adults like them who are high school graduates, have college degrees, are successful in the workplace, and who aren’t incarcerated. If that adult also happens to be a teacher, even better. How do we make that happen though in a school landscape that is a far cry from it right now?

Better recruitment

Here’s a thought: If we aren’t seeing enough diversity in our teaching pool, perhaps we need to try harder to bring them into the industry. This starts before college, though. Young black men of promise in middle and high school should see the field of education as a life path for them. Schools of education at colleges need scholarships to recruit these men and school districts need the extra funding to attract these men when they have their degrees.

The Call Me MISTER Program, first started in South Carolina, has made its way south and onto the campus of Edward Waters College. Starting in 2000 at Clemson University, the Call Me MISTER Program was designed to “increase the pool of available teachers from a broader, more diverse background particular among the State’s lowest performing elementary schools.”

In essence, the program is needed to address the low number of minority male teachers. According to the Department of Education, less than two percent of public teachers nationwide are black men.

This program aims to increase that number by offering scholarships to qualified applicants.

To apply for the program, applicants must have a high school diploma with a 2.5 GPA or better, letters of recommendation, an ACT score of 21 or higher, an SAT score of 1000 or better, and two essays. One to express interest in the program and the other regarding “Why I Want to Teach.”

Why is having more black men in the classroom important? Yes, it’s great for the purpose of diversity and to increase numbers that are tracked by the government. But for many students who need positive black male role models, this program certainly is one of the more important ones offered by our institutions of higher education.

More outreach from the business community

Educators alone simply cannot turn the tide for black boys of color. It’s important that those who have been successful breaking free of poverty or incarceration turn back around and inspire the next generation to do the same.

An example of this in action happened on the first day of school 2015 when 100 men of color wearing suits greeted elementary students of color on their first day of school.

The message these men were trying to send was that if you did work hard and get good grades in school, you’ll eventually find some semblance of the American dream in life. It’s what all kids are taught as they matriculate through grade school. It’s why we so often hear the saying that one should “dress for success.”

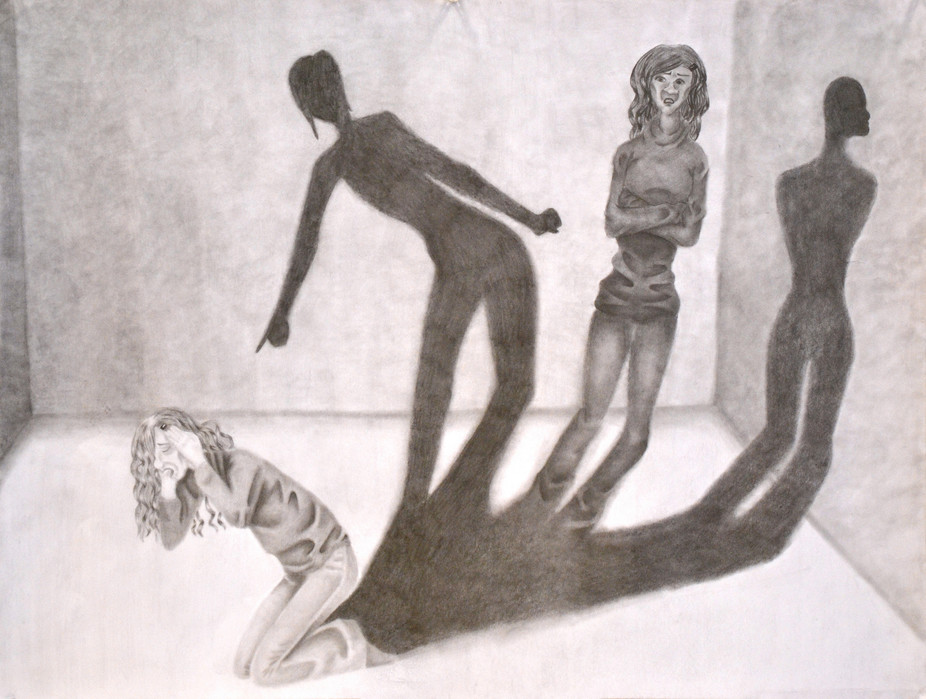

This image contrasts against the statistics, which state that black male “students in grades K-12 were nearly 2 1/2 times as likely to be suspended from school in 2000 as white students” and that most of the nearly 2.5 million people in prisons and jails “are people of color…and people with low levels of educational attainment.”

From pictures to videos, so many kids of color see men of color as effigies of what not to become. The criminal on the news is likely a man of color and so is the high school drop-out. Seeing a roaring crowd of black men cheering on young students from kindergarten to fifth and sixth grades was not only heartwarming, it was inspiring. A suit represents so much more than just a tailored look. It’s success; it’s happiness; it’s an ability to overcome; it’s positive; it’s anti-everything we’ve been feed to believe that’s negative about black men. For each kid seeing that image, it’s eternal.

I applaud this action and know it will have a long-term impact. Now it’s time for more men of means and success to throw their own hats in the ring as mentors and role models.