Middle school students have suffered the largest learning losses related to COVID. Here’s why that may be happening, and how educators can help them recover.

Dr. Gene Kerns

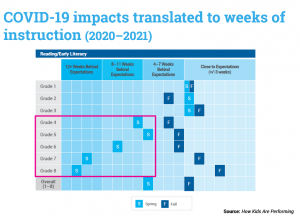

Throughout the pandemic, my colleagues on the Renaissance research team have kept an eye on student performance by comparing the results of millions of Star Assessments with those of previous years. We have shared the findings in our How Kids Are Performing reports. While students across all grades have shown growth during the pandemic-related learning disruptions, that growth hasn’t kept pace with what we’d expect to see in a typical year. According to our most recent data, students in grades 1–8 are about four percentage points below typical performance in reading, though there are a few grades that are a bit more or less behind that average.

Four percentage points may not sound like a lot, but it is significant, and much more so in the later grades than the earlier ones.

In 1st grade, for example, students are seven percentage points behind what we’d expect, but we estimate that it will only take about three weeks of instruction to close that gap. In middle school, on the other hand, we estimate that it will take 12 weeks or more to close the gap.

Academic growth in the earliest grades is quite different from growth in the later grades, even 4th and 5th grade. Younger students can make significant gains very quickly, but the older they get, the longer it generally takes to make similar gains.

Why a Four-Point Gap Is Bigger in Later Grades

Many children start school knowing thousands of words, but with no ability to associate letters and sounds. When you give them the handful of lessons that allow them to begin connecting the universe of words they already know with print, they quickly connect all of that. When we teach children a relatively finite number of phonics skills, it has a very substantial impact on their reading abilities.

That applies to a somewhat lesser extent as children learn the rest of the mechanics of reading, but there are only a certain number of phonemes in the English language. Once you’ve learned them all, becoming a better reader is much harder. It requires reading a lot more and learning more advanced vocabulary words.

The vocabulary words themselves also start becoming much more abstract in middle school. In earliest grades, students begin with concrete words, such as “desk,” “chair,” or “toothbrush.” As they move into middle school, they begin learning more and more abstract words, like “parody.” You can show a student a chair, but how do you teach them the concept of parody? It needs to be explained. With enough context and explanation, students will understand the concept, but it takes more work to learn than concrete words.

The later grades are also when we start asking students to do more abstract thinking about what they are reading. In the first few years, they are largely just reading the words on the page, but in middle school, we start asking them to “read between the lines” and make inferences about what the author is trying to say. One of the best things teachers can do to improve literacy skills at any time, but particularly important in this moment of disruptions, is to support students in extensive reading practice.

Knowledge, Focus Skills, and a Lot of Reading

So much of what we think of as reading ability is really background knowledge. If a student who hasn’t read widely encounters the phrase “Waterloo moment,” for example, they won’t understand that it means a loss after a series of victories. The more widely a student has read, however, the more likely they’ve learned the background knowledge required to understand that phrase and many other allusions.

Another thing teachers can do to help students close the gap is to focus on the skills that are prerequisites for future skills. There’s probably not a teacher in the world who has managed to cover every reading standard for the grade they are teaching in a single year. This year, instead of trying to cover them all, it may make more sense to focus on the ones that provide the greatest returns.

Renaissance has a free resource to help educators prioritize instruction in this way. Focus Skills are those that are absolutely necessary for future learning. Learning phonemes and how to connect them to letters is, for example, a Focus Skill. It’s foundational to reading and writing, and any student who doesn’t learn it will not learn to read. Learning how to alphabetize, on the other hand, is not a Focus Skill. It’s important (and a student who doesn’t learn it will have trouble finding books by their favorite author in the library), but they can still learn to read without it. In time, it’s something they are even likely to pick up on their own along the way.

All literacy skills are important, but with students returning to school from what has been in many ways a lost year, educators will have to make some tough decisions. Like a triage nurse, they must find the areas where they can have the greatest impact to help their students recover what they’ve lost and missed. Middle school students are in the midst of many transitions—from concrete to abstract learning, from elementary to high school, from being children to young adults—and they deserve every tool we can deliver to prepare them for the next step.

Dr. Gene Kerns (@GeneKerns) is vice president and chief academic officer at Renaissance. He is a third-generation educator and has served as a public-school teacher, adjunct faculty member, professional development trainer, district supervisor of academic services, and academic advisor at one of the nation’s top edtech companies. He has trained and consulted internationally and is the co-author of three books. He can be reached at gene.kerns@renaissance.com.